As developers we should always think outside the box. A month ago Artem Zinnatullin and I have discussed some architectural trends on android and on other platforms, like .NET and javascript, in his Podcast The Context. A few days later Christina Lee gave an awesome lightning talk Redux-ing UI Bugs during square’s The Journey of Android Engineers event. She also talked about one of my favorite js libraries: Cycle.js, which defines itself as Model-View-Intent (MVI) library. After watching Christina Lee’s inspiring talk I finally found motivation to take the time to write down my thoughts about MVI on android.

This blog post is outdated. Please take a look at this blog post series about Model-View-Intent.

Preface: Model-View-Intent relies heavily on reactive and functional programming (RxJava). Believe me, many people won’t understand MVI at the first time. I was in the same situation. A year ago, I definitely gave up and started again several times to understand it, but guess what: that’s completely fine! If you don’t understand this blog post at the first go, it’s ok, relax, take it easy and retry it a few days later again.

So what is Model-View-Intent? Yet another architecture for user interfaces? Well, I recommend you to watch the following video about cycle.js presented by the inventor André Medeiros (Staltz) at JSConf Budapest in May 2015 (at least the first 10 minutes) to get a better understanding of the motivation behind MVI:

I know it’s javascript but the key fundamentals are the same for all UI based platforms, incl. android (just replace DOM with android layouts, UI widgets, …).

From MVC to MVI

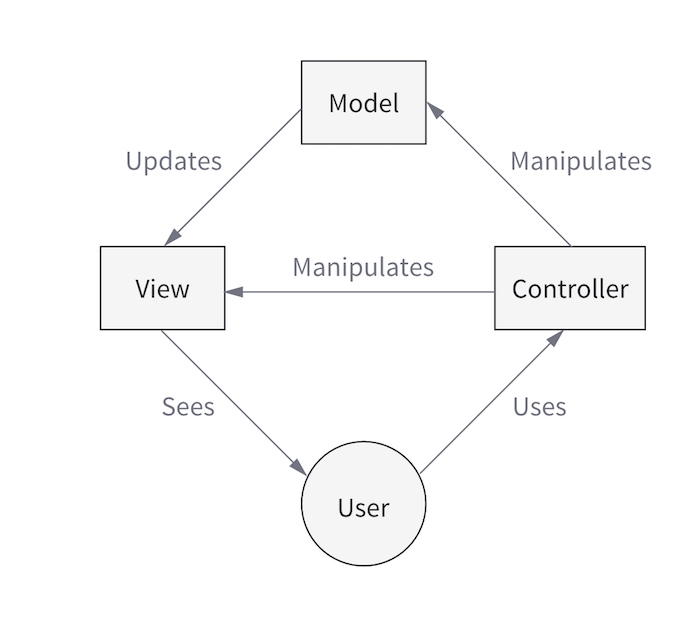

MVI is inspired by some other js frameworks like redux and react, but the key principle comes from Model-View-Controller (MVC). I mean the original MVC introduced 1979 by Trygve Reenskaug to separate View from Model. Again, to clarify, I’m not talking about MVC from iOS (ViewController) or Android (Activity / Fragment) or backend frameworks which also (mis)use the word controller. I talk about MVC in his pure original form. A Model that is observed by the View and a Controller that manipulates the Model. Unlikely nowadays, in Reenskaug original idea of MVC almost every UI element has it’s own Model and Controller. Imagine a CheckBox UI widget: this one observers his own model, i.e. a boolean. The controller could be a OnCheckboxChangedListener triggered by the user’s mouse. From cycle.js docs:

The Controller in MVC is incompatible with our reactive ideals, because it is a proactive component (implying either passive Model or passive View). However, the original idea in MVC was a method for translating information between two worlds: that of the computer’s digital realm and the user’s mental model.

Source: cycle.js.org

However, in the original MVC the controller may or may not also manipulate the view. But that is not exactly what we want, because we want an unidirectional data flow and immutability to establish predictable states, which leads to cleaner, more maintainable code and less bugs.

Source: cycle.js.org

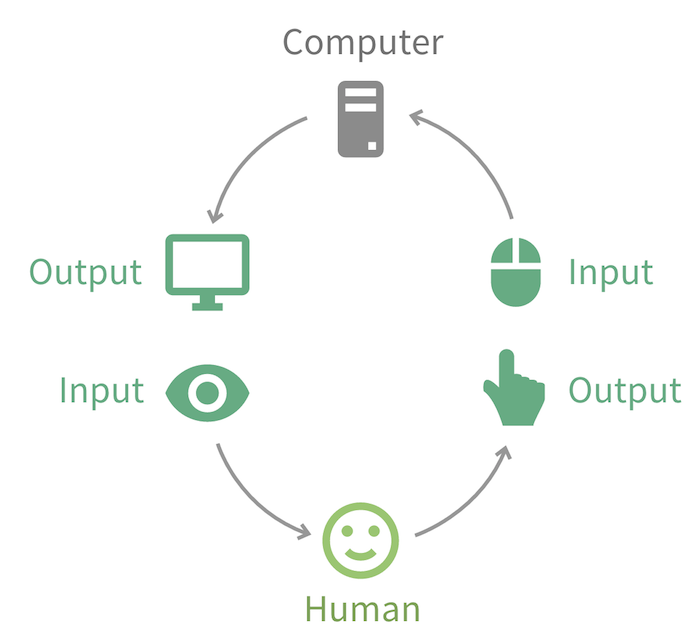

Do you see the unidirectional flow? The cycle? The next question is how do we establish such a circle? Well, as you have seen above, the computer takes an input and converts it to an output (display / view). The human, sees the output from computer and takes it as Input and produces Output (UI widgets events like a click on a button) which then will be again the input for the computer. So the concept of taking a input and have an output seems to be familiar, doesn’t it? Yes, it’s a (mathematical) function.

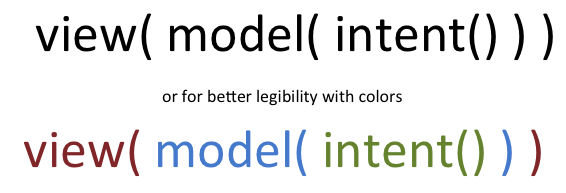

So what we basically want to have is a chain of functions like this:

- intent(): This function takes the input from the user (i.e. UI events, like click events) and translate it to “something” that will be passed as parameter to model() function. This could be a simple string to set a value of the model to or more complex data structure like an Actions or Commands. Here in this blog post we will stick with the word Action.

- model(): The model function takes the output from intent() as input to manipulate the model. The output of this function is a new model (state changed). So it should not update an already existing model. We want immutability! We don’t change an already existing one. We copy the existing one and change the state (and afterwards it can not be changed anymore). This function is the only piece of your code that is allowed to change a Model object. Then this new immutable Model is the output of this function.

- view(): This method takes the model returned from model() function and gives it as input to the view() function. Then the view simply displays this model somehow.

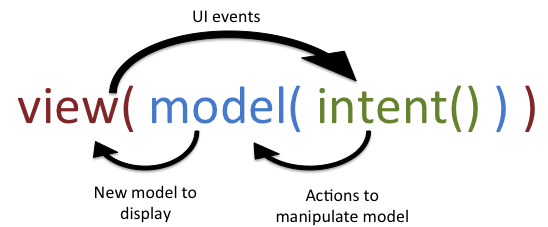

But what about the cycle, one might ask? This is where reactive programming (RxJava, observer pattern) comes in.

So the view will generate “events” (observer pattern) that are passed to the intent() function again.

Sounds quite complex, I know, but once you are into it it’s not that hard anymore. Let’s say we want to build a simple android app to search github (rest api) for repositories matching a certain name. Something like this:

Let’s have a look at a very naive implementation (kotlin). We will use Jake Whartons RxBinding library to get RxJava Observables from SearchView widget. Our data model class looks like this:

data class SearchModel(val searchTerm: String, val results: List<GithubRepo>)

And our main Actvitiy:

class SearchActivity : AppCompatActivity() {

val githubBackend : GitHubBackend = ... ; // Retrofit for Github Rest API

val editSearch: android.widget.SearchView by bindView(R.id.searchView)

val recyclerView: RecyclerView by bindView(R.id.recyclerView)

val loadingView: View by bindView(R.id.loadingView)

var adapter: SearchResultAdapter

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState)

setContentView(R.layout.activity_search)

setSupportActionBar(toolbar)

adapter = SearchResultAdapter(layoutInflater)

recyclerView.adapter = adapter

recyclerView.layoutManager = LinearLayoutManager(this)

// MVI: please note that the following code is chained togehter

// the comments and empty lines are just for legibility

// "intent()" maps UI event to "action" (a search string)

Observable<String> = RxSearchView.queryTextChangeEvents(editSearch)

.filter { it.queryText().count() >= 3 }

.debounce(500, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS) // here: Observable<String>

// "model()" loads data from model

.startWith("") // If starting the first time we emit empty string as Model

.flatMap { queryString ->

if (queryString.isEmpty())

Observable.just( SearchModel("", emptyList)) // returns Observable<SearchModel>

else

githubBackend.search(queryString) // Retrofit; here: Observable<GithubResponse>

.map {

response ->

SearchModel(queryString, response.items)

} // here: Observable<SearchModel>

} // end flatMap; here: Observable<SearchModel>

// "view()" method is just subscribing and updating UI

.observeOn(AndroidSchedulers.mainThread())

.subscribe({ result -> // SearchModel ; onNext()

adapter.items = result.items

adapter.notifyDataSetChanged()

},

{ error -> // onError()

Toast.makeText(...);

}

)

}

}

That’s a lot of code isn’t it. I hope you could follow that code and find my comments helpful. In a nutshell: intent() function basically listens to SearchView Text changes and gives the query string (kind of action to tell the model to search for that string) to the model() function. The model() function is responsible to manage the “model”. With startWith() we ensure that the first time we subscribe to an “empty” search result gets forwarded (in other words, we setup the initial state). Otherwise we use retrofit to load a GithubResponse that we than have to transform to a SearchModel. Last the view() gets the SearchModel as result (RxJava Observer) and is responsible to “render” and display the SearchModel.

Great, we have a unidirectional data flow. Even better, we have immutability and pure functions (none of this function has side effects or stores or changes the state somehow, except retrofit). So are we done?

The Big Picture

What about all the other things we have learned from other architectural design patterns like MVP? What about concepts they offer like separation of concerns, decoupled & maintainable code, testability, reusability, single responsibility and so on?

You get it, this code is basically a common android developer beginner mistake: Put everything in one huge Activity (God object). Well, it has a structure thanks to MVI & RxJava, but is it good code? It’s not spaghetti code (maybe reacitve spaghetti code, that’s a matter of opinion), but is it good code?

Nevertheless, we can do it better. So let’s refactor this code. As you might already know I’m a fan of MVP. So lets combine the best of both, MVP and MVI. In this sample we will use Mosby, a MVP library. Before we start, let’s talk about separation of concerns a little bit. What is the responsibility of the View in MVP? Right, just display the data, and doing what the Presenter “commands” to display. In MVI what should the GUI do? Exactly, the GUI triggers UI events and the intent() function will translate that to “actions” to manipulate the model afterwards.

So the MVP View Interface will offer a intent() function, in our case we call this method searchIntent() function:

interface SearchView : MvpView {

fun searchIntent(): Observable<String> // intent() function

}

Next our Activity will become a MVP View (implements SearchView). That means, everything that is not related to updating the UI or generate UI events will be removed.

class SearchActivity : SearchView, MvpActivity<SearchView, SearchPresenter>() {

val editSearch: android.widget.SearchView by bindView(R.id.searchView)

val recyclerView: RecyclerView by bindView(R.id.recyclerView)

val loadingView: View by bindView(R.id.loadingView)

var adapter: SearchResultAdapter

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState)

setContentView(R.layout.activity_search)

setSupportActionBar(toolbar)

adapter = SearchResultAdapter(layoutInflater)

recyclerView.adapter = adapter

recyclerView.layoutManager = LinearLayoutManager(this)

}

// Provide a intent() function

override fun searchIntent(): Observable<String> {

return RxSearchView.queryTextChangeEvents(editSearch)

.filter { it.queryText().count() >= 3 }

.debounce(500, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS)

}

// dependency injection via dagger

override fun createPresenter(): SearchPresenter = App.getComponent(this).searchPresenter()

}

Ah, looks much better now, doesn’t it? Let’s continue with the Presenter. The Presenters responsibility is to coordinate the view and to be the “bridge” to the business logic. In Mosby, a Presenter has two methods, attachView() (called from activity.onCreate() ) and detachView() (called from activity.onDestroy()).

class SearchPresenter : MvpBasePresenter<SearchView>() {

lateinit var subscription: Subscription

override fun attachView(view: SearchView) {

super.attachView(view)

subscription = view.getSearchIntent() // intent()

.startWith("") // model() function, same as before

.flatMap { queryString ->

if (queryString.isEmpty())

Observable.just( SearchModel("", emptyList)) // returns Observable<SearchModel>

else

githubBackend.search(queryString) // Retrofit; here: Observable<GithubResponse>

.map {

response ->

SearchModel(queryString, response.items)

} // here: Observable<SearchModel>

} // end flatMap; here: Observable<SearchModel>

.observeOn(AndroidSchedulers.mainThread())

.subscribe(view.showData(), view.showError())

}

override fun detachView(retainInstance: Boolean) {

super.detachView(retainInstance)

subscription.unsubscribe()

}

}

Alright, so now the Presenter uses the View’s serachIntent() method and connects it to the model. Are we done? No, the presenter contains the “business logic” code (model() function). So there is one separation of concern still missing. We will refactor that in a minute. Let’s continue with this little statement: .subscribe(view.showData(), view.showError()). Basically this is our view() function. In MVP the Presenter tells the view what to display (“renders” the View). So what are this two methods? This methods are part of the SearchView interface that I have omitted before:

interface SearchView : MvpView {

fun searchIntent(): Observable<String> // intent() function

fun showData(): (SearchModel) -> Unit // RxJava Action1

fun showError(): (Throwable) -> Unit // RxJava Action1

}

class SearchActivity : SearchView, MvpActivity<SearchView, SearchPresenter>() {

...

override fun showData(): (SearchModel) -> Unit = {

adapter.items = it.results

adapter.notifyDataSetChanged()

}

override fun showError(): (Throwable) -> Unit = {

loadingView.visibility = View.GONE

Toast.makeText(this, "An Error has occurred", Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show()

it.printStackTrace()

}

}

So what we now have and what we didn’t had before doing the refactoring is a entirely decoupled View. All the View has to provide is an Observable as intent() function. Today the output of searchIntent() comes from an EditText widget and use debounce() operator. Tomorrow it could be something entirely different (i.e. a dropdown menu with a list of strings to chose from) and you don’t have to touch (and therefore can’t break) anything else of your existing source code except the View (SearchActivity). The same is valid for the way how the view is “rendered” / displayed. All that view related code lives in SearchActivity. Today it uses a RecyclerView to display the “model”, but tomorrow it could be another custom UI widget or a ListView. I guess you get the point.

Back to our Presenter’s source code: as already said, currently the Presenter contains all the business logic. One of the main pitfalls with that is that presenter is not testable (how to mock parts of our business logic) and we can’t reuse that business logic for other Presenter because it’s hard coded. Let’s refactor that code. First we introduce a SearchEngine:

class SearchEngine(private val githubBackend: GithubBackend) {

fun search(query: String): Observable<SearchModel> =

if (query.isEmpty()) {

Observable.just(SearchModel("", emptyList()))

} else {

githubBackend.getRepositories(query).map { SearchModel(query, it.items) }

}

}

SearchEngine gets a GithubBackend and offers a search(String) : Observable for the outside. SearchEngine is our business logic, just functional by providing a search() function with one input (search string) and an output (Observable). In our model() function then we call search engine’s function, who is responsible to change the “model”. The model is basically the search result (initial state is empty list as search result). However, we don’t want to hardcode that again in our Presenter.

What if instead of objects we injection functions?

So we use dependency injection (Dagger) to provide and inject a modelFunc() to other components, in this case to the SearchPresenter:

@Module

class ApplicationModule {

@Provides @Singleton

fun providesSearchEngine(): SearchEngine {

val retrofit = Retrofit.Builder()

.baseUrl("https://api.github.com")

.addConverterFactory(MoshiConverterFactory.create())

.addCallAdapterFactory(RxJavaCallAdapterFactory.create())

.build()

return SearchEngine(retrofit.create(GithubBackend::class.java))

}

@Provides @Singleton

fun providesModelFunc(

searchEngine: SearchEngine): Function1<Observable<String>, Observable<SearchModel>> =

{ stringObservable ->

stringObservable.startWith("").flatMap { queryString -> searchEngine.search(queryString) }

}

}

The important bit here is providesModelFunc() which offers a Lambda Observable -> Observable. Since lambdas are just anonymous functions (kind of) we take this lambda and inject it into SearchPresenter:

class SearchPresenter @Inject constructor(

val modelFunc: (Observable<String>) -> Observable<SearchModel>

) : MvpBasePresenter<SearchView>() {

lateinit var subscription: Subscription

override fun attachView(view: SearchView) {

super.attachView(view)

subscription =

modelFunc( // model()

view.searchIntent() // intent()

)

.observeOn(AndroidSchedulers.mainThread())

.subscribe( // view()

view.showData(),

view.showError()

)

}

override fun detachView(retainInstance: Boolean) {

super.detachView(retainInstance)

subscription.unsubscribe()

}

}

That’s it. we still have view( model( intent() ) ), but this time the view, presenter and “business logic” are super slim, decoupled, reusable, testable and maintainable.

The problem with side effects

Are we done now? Almost. We haven’t discussed yet who is responsible to display and hide the ProgressBar while loading in background data. In MVP it would be the responsibility from Presenter to coordinate the view’s state … ah, the View’s state … do you hear the alarm bells ringing?

Let’s see, how could we do that in MVP? We would simply add a method to the MVP View interface like this:

interface SearchView : MvpView {

...

fun showLoading(): (Any) -> Unit // RxJava Action1

}

class SearchActivity : SearchView, MvpActivity<SearchView, SearchPresenter>() {

...

override fun showData(): (SearchModel) -> Unit = {

adapter.items = it.results

adapter.notifyDataSetChanged()

loadingView.visibility = View.GONE

}

override fun showLoading(): (Any) -> Unit = {

loadingView.visibility = View.VISIBLE

}

}

Then the presenter could do something like this:

class SearchPresenter @Inject constructor(

val modelFunc: (Observable<String>) -> Observable<SearchModel>

) : MvpBasePresenter<SearchView>() {

lateinit var subscription: Subscription

override fun attachView(view: SearchView) {

super.attachView(view)

subscription =

modelFunc( // model()

view.searchIntent() // intent()

.doOnNext(view.showLoading()) // Show loading

)

.observeOn(AndroidSchedulers.mainThread())

.subscribe( // view()

view.showData(),

view.showError()

)

}

override fun detachView(retainInstance: Boolean) {

super.detachView(retainInstance)

subscription.unsubscribe()

}

}

What’s wrong with that code? I mean we do that in MVP all the time, right? The problem is that now our whole system has two states: The view’s state and the state of the model itself. Moreover, the view’s state is caused by a side effect. Do you remember the definition of model() function? Only the model() function is allowed to change the internal application state (with side effects). But the code shown above contradicts with that principle.

So how to solve that? From my point of view there are two options:

The first option is to create a MVI flow just for LoadingView (ProgressBar as View). We talked about MVC’s original definition by Reenskaug. Do you remember? Every GUI widget has it’s own Controller. But who says that every controller has to have his own model? We could share the Model (or observe just a certain part of a model). Guess what, sharing an Observable is pretty easy in RxJava, because there is an operator for that called .share(). So we could have our own MVI / MVP flow with just the ProgressBar as View. In general: we should stop thinking that the whole screen is one huge View with one Controller / Presenter / ViewModel and one underlying Model.

The second option and in my opinion the better option is to have one Model that also propagates his state changes, i.e. before loading data from github the model() function would change the model to it’s internal state “loading”:

data class SearchModel(

val isLoading: Boolean, // true while loading data, false when done

val searchTerm: String,

val results: List<GithubRepo>)

Now SearchEngine would first change the model to SearchModel (true, …) before starting to load the data (and propagate this state change as usual via observable chain which will update the view and finally display the ProgressBar) and then set it to SearchModel (false, …) after having retrieved the new data from github backend.

Screen Orientation Changes

Sir Tony Hoare introduced null references in ALGOL W back in 1965. Retrospective he call this his “Billion Dollar Mistake” (NullpointerException). I think android’s “Billion Dollar Mistake” is to destroy the whole Activity on screen orientation changes. Dealing with screen orientation changes that way it is today in android is really painful. Furthermore, it makes software architecture on android much harder then it has to be.

MVI makes no difference here. On screen orientation changes everything will get lost. So that means that our Model which is representative for the state of a MVI powered app will be lost. We could put that in a retaining Fragment somehow and put it back in right place after screen orientation change. But that only solves half of the problem, because whenever the activity gets destroyed we also have to unsubscribe our observable chain otherwise we will run into memory leaks (we use view.searchIntent()). So what if we start a async background task and want to ensure that it doesn’t get canceled in our model() function? Well we could use .cache() operator or Subjects like ReplaySubject or keep a static map as cache for background tasks. In a nutshell, yes there are ways (I would rather call them workarounds) but I’m not very happy with those solutions. We also have to take into account that our model() function may have to distinguish between initial empty state (.startWith("")) and state after screen orientation changes and process deaths (do we have to make our model Parcelable to save it persistently in a Bundle?). You see, it’s getting out of hand very quickly and introduces more complexity than it has to be.

TL;DR: There might be “workarounds” for screen orientation changes, but I can’t recommend a clean solution for dealing with screen orientation changes on android.

Summary

Model-View-Intent is a very clean way to deal with application states and UI changes. An unidirectional data flow (cycle), predictable states and immutability are the exciting thing about MVI. Composing functions leads to clean and reusable code. I think we can mix MVI with MVP as we did in this example, because I still think that MVP helps to separate your concerns. Furthermore, I can’t highlight enough the importance of a Presentation Model and transforming the Model into a Presentation Model is quite easy with RxJava (just add a .map()) but improves your code a lot and reduces complexity of your View layer.

See the thing with MVI is like with any other software architecture: MVI gives you an idea, but there is still space for personal preferences and interpretation. One can add as many layers as needed. For example, the model() function could internally be composed by multiple functions (one might call them use cases or interactors, just functional). One could add Action data structures to decouple things between intent() and model() even more. But keep in mind: don’t over-engineering things! Software architecture is a continuous evolution:

Stay hungry, stay foolish, think outside the box!

The source code for the sample app shown in this blog post can be found on Github