Once I have figured out that I have modeled my Model classes wrong all the time, a lot of issues and headache I previously had with some Android platform related topics are gone. Moreover, finally I was able to build Reactive Apps using RxJava and Model-View-Intent (MVI) as I never was able before although the apps I have built so far are reactive too but not on the same level of reactiveness as I’m going to describe in this blog post series. In the first part I would like to talk about Model and why Model matters.

So what do I mean with “modeled Models in a wrong way”? Well, there are a lot of architectural patterns out there to separate the “View” from your “Model”. The most popular ones, at least in Android development, are Model-View-Controller (MVC), Model-View-Presenter (MVP) and Model-View-ViewModel (MVVM). Do you notice something by just looking at the name of these patterns? They all talk about a “Model”. I realized that most of the time I didn’t have a Model at all.

Example: Just load a list of persons from a backend. A “traditional” MVP implementation could look like this:

class PersonsPresenter extends Presenter<PersonsView> {

public void load(){

getView().showLoading(true); // Displays a ProgressBar on the screen

backend.loadPersons(new Callback(){

public void onSuccess(List<Person> persons){

getView().showPersons(persons); // Displays a list of Persons on the screen

}

public void onError(Throwable error){

getView().showError(error); // Displays a error message on the screen

}

});

}

}

But where or what is the “Model”? Is it the backend? No, that is business logic. Is it the result List<Person>? No, that is just one thing our View displays amongst others like a loading indicator or an error message. So, what actually is the “Model”?

From my point of view there should be a “Model” class like this:

class PersonsModel {

// In a real application fields would be private

// and we would have getters to access them

final boolean loading;

final List<Person> persons;

final Throwable error;

public(boolean loading, List<Person> persons, Throwable error){

this.loading = loading;

this.persons = persons;

this.error = error;

}

}

And then the Presenter could be implemented like this:

class PersonsPresenter extends Presenter<PersonsView> {

public void load(){

getView().render( new PersonsModel(true, null, null) ); // Displays a ProgressBar

backend.loadPersons(new Callback(){

public void onSuccess(List<Person> persons){

getView().render( new PersonsModel(false, persons, null) ); // Displays a list of Persons

}

public void onError(Throwable error){

getView().render( new PersonsModel(false, null, error) ); // Displays a error message

}

});

}

}

Now the View has a Model which then will be “rendered” on the screen. This concept is not really something new. The original MVC definition by Trygve Reenskaug from 1979 had quite a similar concept: The View observes the Model for changes. Unfortunately, the term MVC has been (mis)used to describe too many different patterns that are not really the same what Reenskaug formulated in 1979. For instance, backend developers use MVC frameworks, iOS has ViewController and what does MVC on Android actually mean? Activities are Controller? What is a ClickListener then? Nowadays the term MVC is just a big mistake, misusage and misinterpretation of what Reenskaug originally formulated. But let’s stop this discussion about MVC here, this could run out of control.

Let’s come back to what I have claimed at the beginning. Having a “Model” solves a lot of issues we quite often struggle with in Android development:

- The State Problem

- Screen orientation changes

- Navigation on the back stack

- Process death

- Immutability and unidirectional data flow

- Debuggable and reproducible states

- Testability

Let’s discuss these points and let’s see how “traditional” implementations of MVP and MVVM deal with these problems and finally how a “Model” can help to prevent common pitfalls.

1. The State Problem

Reactive Apps - this is a buzzword, isn’t it? With that I mean are apps with a UI that react on state changes. Ah, here we have another nice word: “State”. What is “State”? Well, most of the time we describe “State” as what we see on the screen, like “loading state” when the View displays a ProgressBar. Therein lies the crux: we frontend developers tend to be focused on UI. That is not necessarily a bad thing because at the end of the day a good UI decides whether or not a User will use our app and therefore how successful an app is. But take a look at the very basic MVP code example from above (not the one using PersonsModel). Here the state of the UI is coordinated by the Presenter, since the Presenter tells the View what to display. The same is true for MVVM. In this blog post I want to distinguish between two MVVM implementations: The first one with Android’s data binding and the second option using RxJava. In MVVM with data binding the state directly sits in the ViewModel:

class PersonsViewModel {

ObservableBoolean loading;

// ... Other fields left out for better readability

public void load(){

loading.set(true);

backend.loadPersons(new Callback(){

public void onSuccess(List<Person> persons){

loading.set(false);

// ... other stuff like set list of persons

}

public void onError(Throwable error){

loading.set(false);

// ... other stuff like set error message

}

});

}

}

In MVVM with RxJava we don’t use the data binding engine but bind Observable to UI Widgets in the View, for example:

class RxPersonsViewModel {

private PublishSubject<Boolean> loading;

private PublishSubject<List<Person> persons;

private PublishSubject loadPersonsCommand;

public RxPersonsViewModel(){

loadPersonsCommand.flatMap(ignored -> backend.loadPersons())

.doOnSubscribe(ignored -> loading.onNext(true))

.doOnTerminate(ignored -> loading.onNext(false))

.subscribe(persons)

// Could also be implemented entirely different

}

// Subscribed to in View (i.e. Activity / Fragment)

public Observable<Boolean> loading(){

return loading;

}

// Subscribed to in View (i.e. Activity / Fragment)

public Observable<List<Person>> persons(){

return persons;

}

// Whenever this action is triggered (calling onNext() ) we load persons

public PublishSubject loadPersonsCommand(){

return loadPersonsCommand;

}

}

Of course these code snippets are not perfect and your implementation may look entirely different. The point is that usually in MVP and MVVM the state is driven by either the Presenter or the ViewModel.

This leads to the following observations:

- The business logic has its own state, the Presenter (or ViewModel) has its own state (and you try to sync the state of business logic and Presenter so that both have the same state) and the View may also have its own state (i.e. you set the visibility somehow directly in the View, or Android itself restores the state from bundle during recreation).

- A Presenter (or ViewModel) has arbitrarily many inputs (the View triggers an action handled by Presenter) which is ok, but a Presenter also has many outputs (or output channels like view.showLoading() or view.showError() in MVP or ViewModel is offering multiple Observables) which eventually leads to conflicting states of View, Presenter and business logic especially when working with multiple threads.

In the best-case scenario, this only results in visual bugs such as displaying a loading indicator (“loading state”) and error indicator (“error state”) at the same time like this:

In the worst-case scenario, you have a serious bug reported to you from a crash reporting tool like Crashlytics, that you are not able to reproduce and therefore making it almost impossible to fix.

What if we only have one single source of truth for state passed from bottom (business logic) to the top (the View). Actually, we have already seen a similar concept at the very beginning of this blog post when we talked about “Model”.

class PersonsModel {

// In a real world application those fields would be private

// and we would have getters to access them

final boolean loading;

final List<Person> persons;

final Throwable error;

public(boolean loading, List<Person> persons, Throwable error){

this.loading = loading;

this.persons = persons;

this.error = error;

}

}

Guess what? Model reflects the State. Once I have understood this, a lot of state related issues were solved (and prevented from the very beginning) and suddenly my Presenter has exactly one output: getView().render(PersonsModel). This reflects a simple mathematical function like f(x) = y (also possible with multiple inputs i.e. f(a,b,c), exactly one output). Math might not be everyone’s cup of tea, but a mathematician doesn’t know what a bug is. Software Engineers do.

Understanding what a “Model” is and how to model it properly is important, because at the end a Model can solve the “State Problem”

2. Screen orientation changes

In Android screen orientation change is a challenging problem. The simplest way to deal with that is to ignore it. Just reload everything on each screen orientation change. This is a completely valid solution. Most of the time your app works offline too so that data comes from a local database or another local cache. Therefore, loading data is super-fast after screen orientation changes. However, I personally dislike seeing a loading indicator, even if it’s just for a few milliseconds, because in my opinion this is not a seamless user experience. So people (including myself) started to use MVP with “retaining presenter” so that a View can be detached (and destroyed) during screen orientation changes, whereas the Presenter survives in memory and then the View gets reattached to the Presenter. The same concept is possible with MVVM with RxJava, but we have to keep in mind that once a View gets unsubscribed from his ViewModel the observable stream is destroyed. You could work around this with Subjects for example. In MVVM with data binding a ViewModel is directly bound to the View by the data binding engine himself. To avoid memory leaks we have to destroy the ViewModel on screen orientation changes.

But the problem with retaining Presenter (or ViewModel) is: how do we bring the View’s state back to the same state as it was before the screen orientation change, so that both, View and Presenter, are in the same state again? I have written a MVP library called Mosby with a feature called ViewState which basically synchronizes the state of your business logic with the View. Moxy, another MVP library, implemented a quite interesting solution by using “commands” to reproduce the View’s state after a screen orientation change:

Image borrowed from https://github.com/Arello-Mobile/Moxy

I’m pretty sure that there are also other solutions for the View’s state problem out there. Let’s take a step back and summarize the issue those libraries try to solve: They try to solve the problem of state which we have already discussed.

So, again, having one “Model” which reflects the current “State” and exactly one method to “render” the “Model” solves this problem as easy as calling getView().render(PersonsModel) (with the latest Model when reattaching the View to Presenter).

3. Navigation on the back stack

Does a Presenter (or ViewModel) need to be kept when the View is not in use anymore? For instance, if the Fragment (View) has been replaced with another Fragment because the user has navigated to another screen, then there is no View attached to the Presenter. If no View is attached a Presenter obviously can’t update the View with the latest data from business logic. What if the user comes back (i.e. pressing the back button to pop the back stack)? Reload the data or reuse the existing Presenter? This is more a philosophical question. Usually once the user comes back to a previous screen (pop back stack) he would expect to continue where he left off. This is basically the “restore View’s state problem” as discussed in 2. So the solution is straightforward: With a “Model” representing the state we just call getView().render(PersonsModel) to render the View when coming back from back stack.

4. Process death

I think it is a common misunderstanding in Android development that process death is a bad thing and that we need libraries that help us to restore state (and Presenters or ViewModels) after process death. First, a process death only ever happens for a good reason: the Android operating system needs more resources for other apps or to save battery. But this will never happen when your app is in the foreground and is being actively used by your app’s user. So be a good citizen and don’t fight against the platform. If you really have some long running work to do in the background use a Service as this is the only way to signal the operating system that your app is still “actively used”. If a process death happens Android provides some callbacks like onSaveInstanceState() to save the state. Again, State. Should we save our View information into the Bundle? Does the Presenter have its own state we have to save into the bundle too? What about business logic state? We already had this dance: As described in 1. 2. and 3. we only need a Model class that is representing the whole state. Then it’s easy to save this Model into a bundle and to restore it afterwards. However, I personally think that most of the time it is better to not save the state but rather reload the whole screen just like we are doing on first app start. Think of a NewsReader app displaying a list of news articles. When our app is killed and we save the state and 6 hours later the user reopens our app and the state is restored, our app may display outdated content. Maybe not storing the Model / State and simply reloading the data is better in this scenario.

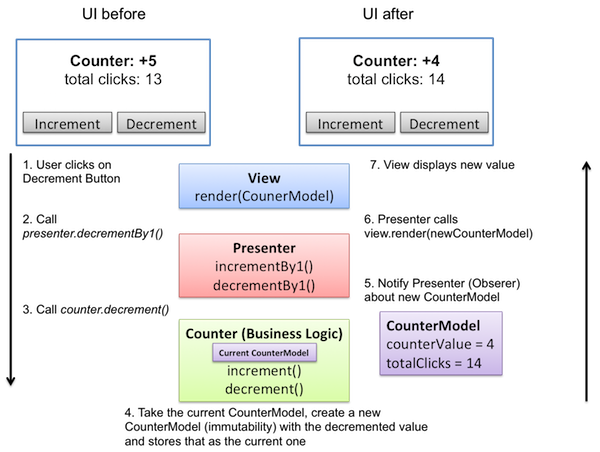

5. Immutability and unidirectional data flow

I’m not going to talk about the advantage of immutability because there are a lot of resources available about this topic. We want an immutable “Model” (which is representing the state). Why? Because we want only one single source of truth. We don’t want that other components in our app can manipulate our Model / State as we pass the Model object around. Let’s imagine we are going to write a simple “counter” Android app that has an increment and decrement button and displays the current counter value in a TextView. If our Model (which in this case is just the counter value - an integer) is immutable, how do we change the counter? I’m glad you asked. We are not manipulating the TextView directly on each button click. Some observations: First, our View should just have a view.render(…). Second, our model is immutable, so no direct change of Model is possible. Third, there is only one single source of truth: the business logic. We let click events “sink down” to the business logic. The business logic knows the current Model (i.e. has a private field with the current Model) and will create a new Model with the incremented / decremented value according to the old Model.

By doing so we have established a unidirectional data flow with the business logic as single source of truth which creates immutable Model instances. But this seems so over engineered for just a simple counter, doesn’t it? Yes, a counter is just a simple app. Most apps start as a simple app but then the complexity grows fast. A unidirectional data flow and an immutable model is necessary from my point of view even for simple apps to ensure they stay simple (from developers point of view) when complexity grows.

6. Debuggable and reproducible states

Moreover, the unidirectional data flow ensures that our app is easy to debug. Wouldn’t it be nice next time we get a crash report from Crashlytics that we could reproduce and fix this crash easily because all required information is attached to that crash report. What is “the required information”? Well, all information we need is the current Model and the action the user wanted to perform when the crash happened (i.e. clicked decrement Button). That’s all we need to reproduce this crash and that information is super easy to log and to attach to a crash report. This would not be as easy without a unidirectional data flow (i.e. someone misuses an EventBus and fires CounterModels out into the wild) or without immutability (so that we are not sure who has actually changed the Model).

7. Testability

“Traditional” MVP or MVVM improves testability of an app. MVC is also testable: nobody ever said that we have to put all our business logic into the activity. With a Model representing State we can simplify our unit test’s code as we can simply check assertEquals(expectedModel, model). This eliminates a lot of objects we otherwise have to mock. Additionally, this removes many verification tests that a certain method has been called i.e. Mockito.verify(view, times(1)).showFoo(). Eventually, this makes our unit test’s code more readable, understandable and finally maintainable as we don’t have to deal that much with implementation details of our real code.

Conclusion

In this first part of this blog post series we talked a lot about theoretical stuff. Do we really need a dedicated blog post about Model? I think it is elementary to understand that a Model is important and helps to prevent some issues we otherwise would struggle with. Model doesn’t mean business logic. It’s the business logic (i.e. an Interactor, a Usecase, a Repositor or whatever you call it in your app) that produces a Model. In the second part we will see this theoretical Model stuff in action when we finally build a reactive app with Model-View-Intent. The demo app we are going to build is a app for a fictional online shop. Here is just a short preview demo of what you can expect in part two. Stay tuned.

This is a post in the Reactive Apps with Model-View-Intent series.

Other posts in this series:

- Reactive Apps with Model-View-Intent - Part 1: Model

- Reactive Apps with Model-View-Intent - Part 2: View and Intent

- Reactive Apps with Model-View-Intent - Part 3: State Reducer

- Reactive Apps with Model-View-Intent - Part 4: Independent UI Components

- Reactive Apps with Model-View-Intent - Part 5: Debugging with ease

- Reactive Apps with Model-View-Intent - Part 6: Restoring State

- Reactive Apps with Model-View-Intent - Part 7: Timing (SingleLiveEvent problem)

- Reactive Apps with Model-View-Intent - Part 8: Navigation