In the first part we have discussed what a Model actually is, the relation to State and how a well defined Model can solve some common issues in android development. In this blog post we continue our journey towards “Reactive Apps” by introducing the Model-View-Intent pattern to build Reactive Apps.

If you haven’t read part 1 yet, you should read that before continue with this blog post. To summarize: Rather then writing code like this (for example in “traditional” MVP)

class PersonsPresenter extends Presenter<PersonsView> {

public void load(){

getView().showLoading(true); // Displays a ProgressBar on the screen

backend.loadPersons(new Callback(){

public void onSuccess(List<Person> persons){

getView().showPersons(persons); // Displays a list of Persons on the screen

}

public void onError(Throwable error){

getView().showError(error); // Displays a error message on the screen

}

});

}

}

we should create a “Model” that reflects the “State”:

class PersonsModel {

// In a real application fields would be private

// and we would have getters to access them

final boolean loading;

final List<Person> persons;

final Throwable error;

public(boolean loading, List<Person> persons, Throwable error){

this.loading = loading;

this.persons = persons;

this.error = error;

}

}

And then the Presenter could be implemented like this:

class PersonsPresenter extends Presenter<PersonsView> {

public void load(){

getView().render( new PersonsModel(true, null, null) ); // Displays a ProgressBar

backend.loadPersons(new Callback(){

public void onSuccess(List<Person> persons){

getView().render( new PersonsModel(false, persons, null) ); // Displays a list of Persons

}

public void onError(Throwable error){

getView().render( new PersonsModel(false, null, error) ); // Displays a error message

}

});

}

}

Now the View has a Model which then will be “rendered” on the screen simply by invoking render(personsModel). In the first part we also talked about the importance of an unidirectional data flow and that your business logic should drive this model. Before we start to connect the dots lets quickly discuss the main idea of MVI.

Model-View-Intent (MVI)

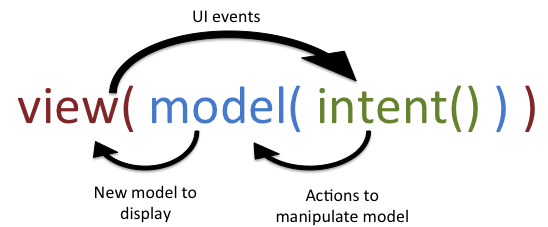

This pattern was specified by André Medeiros (Staltz) for a JavaScript framework he has written called cycle.js. From a theoretical (and mathematical) point of view we could describe Model-View-Intent as follows:

- intent(): This function takes the input from the user (i.e. UI events, like click events) and translate it to “something” that will be passed as parameter to model() function. This could be a simple string to set a value of the model to or more complex data structure like an Object. We could say we have the intention to change the model with an intent.

- model(): The model() function takes the output from intent() as input to manipulate the Model. The output of this function is a new Model (state changed). So it should not update an already existing Model. We want immutability! In the first part I gave a concrete example with a “counter app”. Again, we don’t change an already existing Model object instance. We create a new Model according to the changes described by the intent. Please note, that the model() function is the only piece of your code that is allowed to create a new Model object. Then this new immutable Model is the output of this function. Basically, the model() function calls our apps business logic (could be an Interactor, Usecase, Repository … whatever pattern / terminology you use in your app) and delivers a new Model object as result.

- view(): This method takes the model returned from model() function and gives it as input to the view() function. Then the View simply displays this Model somehow. view() is basically the same as view.render(model).

But we want to build a “Reactive App”, don’t we? So how is MVI “reactive”? What does “reactive” actually means in this context? With “reactive” we mean apps with a UI that reacts on state changes. Since “State” is reflected by a “Model” essentially we want that our Business logic “reacts” on input events (intents) and produces a “Model” as output which then can be displayed in the View by calling view’s render(model) method.

Connecting the dots with RxJava

We want that our data flows unidirectional. Here comes RxJava into play. Do we need RxJava to build reactive apps with an unidirectional data flow or MVI based apps? No, we could also write imperative and procedural code. However, RxJava is very good for event based programming. Since UI are event based too using RxJava makes a lot of sense.

In this blog post we are going to build a simple app for a fictional online shop. We make http requests to a backend to load products that we display in the app. We can search for certain products and add products into a shopping basket. Overall the final app looks like this:

The source code can be found on github. Let’s start by implementing a simple screen: Let’s implement the search. First, we define a Model which at the end is displayed by the View as described in Part 1 of this blog post series. In this blog post series we give all our Model classes a “ViewState” suffix, i.e. our Model class for the screen to search for products in our online shop app is called SearchViewState because the Model reflects the State. Also alternative names like SearchModel sounds a little bit strange or SearchViewModel could lead to confusion with MVVM. Naming is hard.

public interface SearchViewState {

/**

* The search has not been stared yet

*/

final class SearchNotStartedYet implements SearchViewState {

}

/**

* Loading: Currently waiting for search result

*/

final class Loading implements SearchViewState {

}

/**

* Indicates that the search has delivered an empty result set

*/

final class EmptyResult implements SearchViewState {

private final String searchQueryText;

public EmptyResult(String searchQueryText) {

this.searchQueryText = searchQueryText;

}

public String getSearchQueryText() {

return searchQueryText;

}

}

/**

* A valid search result. Contains a list of items that have matched the searching criteria.

*/

final class SearchResult implements SearchViewState {

private final String searchQueryText;

private final List<Product> result;

public SearchResult(String searchQueryText, List<Product> result) {

this.searchQueryText = searchQueryText;

this.result = result;

}

public String getSearchQueryText() {

return searchQueryText;

}

public List<Product> getResult() {

return result;

}

}

/**

* Indicates that an error has occurred while searching

*/

final class Error implements SearchViewState {

private final String searchQueryText;

private final Throwable error;

public Error(String searchQueryText, Throwable error) {

this.searchQueryText = searchQueryText;

this.error = error;

}

public String getSearchQueryText() {

return searchQueryText;

}

public Throwable getError() {

return error;

}

}

}

Since Java is a strongly typed language we have chosen a type safe approach for our Model class by splitting each “sub-state” in its own class. Our business logic returns an object of type SearchViewState which could be an instance of SearchViewState.Error etc. This is just a personal preference. We could have also modeled this entirely different, for example:

class SearchViewState {

Throwable error; // if not null, an error has occurred

boolean loading; // if true loading data is in progress

List<Product> result; // if not null this is the result of the search

boolean SearchNotStartedYet; // if true, we have the search not started yet

}

Again, how you model your Models is just a matter of personal preferences. If you use the kotlin programming language then sealed classes are a great choice.

Next, let’s focus on the Business Logic. Let’s introduce a SearchInteractor which is responsible to execute the search. As already said the “output” is a SearchViewState object.

public class SearchInteractor {

final SearchEngine searchEngine; // Makes http calls

public Observable<SearchViewState> search(String searchString) {

// Empty String, so no search

if (searchString.isEmpty()) {

return Observable.just(new SearchViewState.SearchNotStartedYet());

}

// search for products

return searchEngine.searchFor(searchString) // Observable<List<Product>>

.map(products -> {

if (products.isEmpty()) {

return new SearchViewState.EmptyResult(searchString);

} else {

return new SearchViewState.SearchResult(searchString, products);

}

})

.startWith(new SearchViewState.Loading())

.onErrorReturn(error -> new SearchViewState.Error(searchString, error));

}

}

Let’s take a look at the method signature of SearchInteractor.search(): We have String searchString as input parameter and Observable<SearchViewState> as output. This already hints that we expect that arbitrary many instances of SearchViewState are emitted on this observable stream over time. startWith() says before we are actually starting the search query (via SearchEngine which executes the http request) we emit SearchViewState.Loading. At the end this will force the View to display a ProgressBar while executing the search.

onErrorReturn() catches any Exceptions that may occur while executing the search and emits a SearchViewState.Error. Couldn’t we just use the onError callback when we subscribe to this Observable? This is a common misunderstanding in RxJava: the error callback is meant to be used when the whole observable stream runs into an unrecoverable error and therefore the observable stream terminates. In our case an error like no active internet connection is not an unrecoverable error. It is yet just another state represented by our Model. Furthermore, we can move to another state afterwards i.e. once the an active internet connection is available we can move to the “loading state” represented by SearchViewState.Loading . So we establish an observable stream from our business logic to our view emitting a changed Model every time the “State” changes. We certainly don’t want to terminate this observable stream on a internet connection error. Therefore, such errors are handled as a State (rather than a fatal error that terminates the stream) which is reflected by the Model and emitted to the observable stream when an error occurs. Usually in MVI the Model Observable never terminates (never reaches the subscriber’s onComplete() or onError() ).

To sum it up: SearchInteractor (business logic) offers an observable stream Observable<SearchViewState> and emits a new SearchViewState every time the state changes.

Next let’s discuss how our View layer looks like. What should the View do? Well, obviously the view should display the Model. We have agreed that the View should have a function like render(model). Additionally, the view should offer a way for other layers to react on user input events. These are called intents in MVI. In our case there is only one intent: the user can search for a product by typing a String into a input field. We implement MVI in a similar way to MVP. It is good practice in MVP to define a interface for the View layer so let’s do this in MVI too.

public interface SearchView {

/**

* The search intent

*

* @return An observable emitting the search query text

*/

Observable<String> searchIntent();

/**

* Renders the View

*

* @param viewState The current viewState state that should be displayed

*/

void render(SearchViewState viewState);

}

In this case our View only offers one intent but in general a View could offer multiple intents. In part 1 we have discussed why a single render() function is a nice approach, if it is unclear why we should prefer a single render() you should read part 1 again (or leave a comment below; see also comment section in part 1). Before we start with the concrete implementation of the View layer, let’s take a look how the final result should look like:

public class SearchFragment extends Fragment implements SearchView {

@BindView(R.id.searchView) android.widget.SearchView searchView;

@BindView(R.id.container) ViewGroup container;

@BindView(R.id.loadingView) View loadingView;

@BindView(R.id.errorView) TextView errorView;

@BindView(R.id.recyclerView) RecyclerView recyclerView;

@BindView(R.id.emptyView) View emptyView;

private SearchAdapter adapter;

@Override public Observable<String> searchIntent() {

return RxSearchView.queryTextChanges(searchView) // Thanks Jake Wharton :)

.filter(queryString -> queryString.length() > 3 || queryString.length() == 0)

.debounce(500, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS);

}

@Override public void render(SearchViewState viewState) {

if (viewState instanceof SearchViewState.SearchNotStartedYet) {

renderSearchNotStarted();

} else if (viewState instanceof SearchViewState.Loading) {

renderLoading();

} else if (viewState instanceof SearchViewState.SearchResult) {

renderResult(((SearchViewState.SearchResult) viewState).getResult());

} else if (viewState instanceof SearchViewState.EmptyResult) {

renderEmptyResult();

} else if (viewState instanceof SearchViewState.Error) {

renderError();

} else {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Don't know how to render viewState " + viewState);

}

}

private void renderResult(List<Product> result) {

TransitionManager.beginDelayedTransition(container);

recyclerView.setVisibility(View.VISIBLE);

loadingView.setVisibility(View.GONE);

emptyView.setVisibility(View.GONE);

errorView.setVisibility(View.GONE);

adapter.setProducts(result);

adapter.notifyDataSetChanged();

}

private void renderSearchNotStarted() {

TransitionManager.beginDelayedTransition(container);

recyclerView.setVisibility(View.GONE);

loadingView.setVisibility(View.GONE);

errorView.setVisibility(View.GONE);

emptyView.setVisibility(View.GONE);

}

private void renderLoading() {

TransitionManager.beginDelayedTransition(container);

recyclerView.setVisibility(View.GONE);

loadingView.setVisibility(View.VISIBLE);

errorView.setVisibility(View.GONE);

emptyView.setVisibility(View.GONE);

}

private void renderError() {

TransitionManager.beginDelayedTransition(container);

recyclerView.setVisibility(View.GONE);

loadingView.setVisibility(View.GONE);

errorView.setVisibility(View.VISIBLE);

emptyView.setVisibility(View.GONE);

}

private void renderEmptyResult() {

TransitionManager.beginDelayedTransition(container);

recyclerView.setVisibility(View.GONE);

loadingView.setVisibility(View.GONE);

errorView.setVisibility(View.GONE);

emptyView.setVisibility(View.VISIBLE);

}

}

The render(SearchViewState) method should be self explaining. In searchIntent() we use Jake Wharton’s RxBindings library that provides RxJava bindings like Observable for Android UI widget. RxSearchView.queryText() creates an Observable<String> that emits the search string every time the user types something into the EditText UI widget. We use filter() to only start a search query if the user has typed in more than 3 characters and we don’t want hit the backend every time the user types in a new character but rather we want to wait until the user has finished typing (debounce() waits 500 milliseconds to determine if the user has finished typing).

So we know that the “input” for this screen is the searchIntent() and that render() is the “output”. How do we get from “input” to “output”? The following video visualizes that:

The remaining question is who or how do we connect the View’s intent with the business logic? If you take a closer look at the video from above you will see that there is a flatMap() operator in the middle. This already hints us that there is an additional component involved we haven’t talked about yet: a Presenter. The Presenter is responsible to connect the dots similar as we would use a presenter in MVP.

public class SearchPresenter extends MviBasePresenter<SearchView, SearchViewState> {

private final SearchInteractor searchInteractor;

@Override protected void bindIntents() {

Observable<SearchViewState> search =

intent(SearchView::searchIntent)

.switchMap(searchInteractor::search) // I have used flatMap() in the video above, but switchMap() makes more sense here

.observeOn(AndroidSchedulers.mainThread());

subscribeViewState(search, SearchView::render);

}

}

Please node that SearchView::searchIntent is just a Java 8 shorthand for searchView.searchIntent()

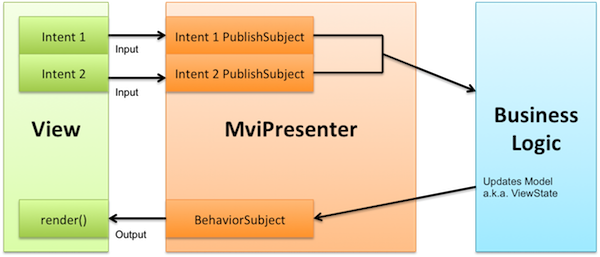

What is MviBasePresenter and what are intent() and subscribeViewState()? This class is part of a library I have written called Mosby (Mosby 3.0 has a MVI module). This blog post is not about Mosby but I want briefly talk about how MviBasePresenter works to convince you that there is no black magic involved although I have to admit that at first glance it looks like that. Let’s start with lifecycle: MviBasePresenter doesn’t really have a lifecyle. There is a bindIntent() method where you bind the intents from the View to the business logic. Typically, you use flatMap() or switchMap() or concatMap() to “forward” an intent to the business logic. This method is invoked only the first time a View is attached to the Presenter. It’s not invoked again when the View gets reattached (i.e. after a screen orientation change).

That may sounds a bit strange and one may ask: “Does MviBasePresenter even survive screen orientation changes and if yes how does Mosby ensures that the observable stream remains without leaking the memory?” This is what intent() and subscribeViewState() are for. intent() creates a PublishSubject internally and uses that one as “gateway” to your business logic. So actually this PublishSubject is subscribing to View’s intent Observable. Calling intent(o1) actually returns a PublishSubject which is subscribed to o1.

On orientation change Mosby detaches the View from Presenter but only unsubscribes this internal PublishSubject temporarily from the View and resubscribes the PublishSubject to the View’s intent when the view gets reattached to the presenter.

subscribeViewState() does the same but the other way around (Presenter to View communication). It creates internally a BehaviorSubject as “gateway” from business logic to View. Since it’s a BehaviorSubject we can receive “model updates” from business logic even if no view is attached at the moment (i.e. View is on the back stack). BehaviorSubjects always keep the latest value it has received and replays that once the View gets reattached.

The rule is simple: use intent() to “wrap” any intent of the view. Use subscribeViewState() instead of Observable.subscribe(…).

The counter part to bindIntent() is unbindIntents() which is invoked exactly one time the View is destroyed permanently. For instance putting a fragment on the back stack doesn’t destroy the View permanently, but finishing an Activity does. Since intent() and subscribeViewState() already take care of subscription management you only barely need to implement unbindIntents().

What about other lifecycle events like onPause() or onResume()? I still think that Presenters don’t need lifecycle Events. However, if you really think you need them you can simply see a lifecycle event like onPause() as an intent. Your View could offer a pauseIntent() which is triggered by android lifecycle instead of a user interaction intent like clicking on a button. But both are valid intents.

Conclusion

In this second part we have talked about the basics of Model-View-Intent and implemented a very simple screen by using MVI to get our feet wet. Maybe this example is too simple so that you don’t fully see yet the benefits of MVI pattern, a Model which represents State and the unidirectional data flow compared to “traditional” MVP or MVVM. There is nothing wrong with MVP or MVVM and I’m not saying that MVI is better than other architectural patterns. However, I think that MVI helps us to write elegant code for complex problems as we will see in the next part (Part 3) of this blog series when we are going to talk about state reducers.

This is a post in the Reactive Apps with Model-View-Intent series.

Other posts in this series:

- Reactive Apps with Model-View-Intent - Part 1: Model

- Reactive Apps with Model-View-Intent - Part 2: View and Intent

- Reactive Apps with Model-View-Intent - Part 3: State Reducer

- Reactive Apps with Model-View-Intent - Part 4: Independent UI Components

- Reactive Apps with Model-View-Intent - Part 5: Debugging with ease

- Reactive Apps with Model-View-Intent - Part 6: Restoring State

- Reactive Apps with Model-View-Intent - Part 7: Timing (SingleLiveEvent problem)

- Reactive Apps with Model-View-Intent - Part 8: Navigation